Railways and Italians in the Pacific Northwest

Much like mining and construction, railways and Italians are intertwined in Northwest history

I've been working on the railroad

All the live-long day.

I've been working on the railroad

Just to pass the time away.

Ballad of America, Inc., a non-profit whose mission is to “preserve and celebrate music from America’s diverse cultural history” tells us that this song was “adapted late in the 19th century either from an African-American spiritual about working on a Mississippi River levee or from an old Irish hymn.”

The upbeat melody and lyrics bring a certain nostalgia to the tune, and yet for many immigrants to America, including Italians, working on the railroad was definitely not something they undertook to “just pass the time away.” Though there’s also no record I know of Italians ever singing that specific song, I like to imagine they did sing folk songs from La Bel Paese. During the countless, monotonous days they spent building our nation’s iron tracks, they needed something besides “strong mud” (bad coffee in hobo slang) to help them stay awake and motivated.

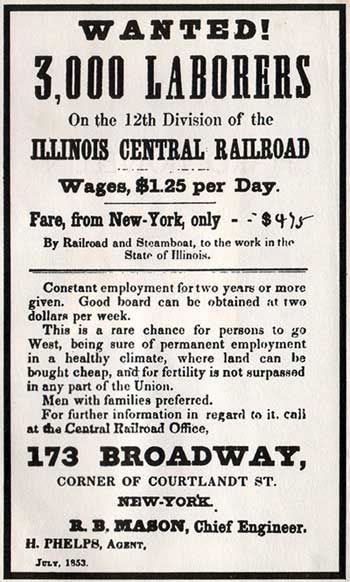

Once President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862, thus began America’s industrial might and Italian laborers’ part in it. Though the country was still divided after the war, a railroad that would (eventually) run from coast to coast galvanized the nation. With the coming of the transcontinental railroad after the end of the Civil War, America needed laborers and Italians contributed much blood, sweat, and tears to the effort. The first transcontinental was the longest at nearly 2,000 miles, though as early as 1860, America already had over 30,000 miles, spread mostly over the Northeast and Midwest.

Many Italian immigrant men, usually single, came to the United States to work on the railroads, most under the padrone system. Not the best job, but surely the easiest job to get if you were an unskilled laborer. These men may have left the Island of Tears—what Italians called Ellis Island—with hope in their heart, though they probably couldn’t imagine the reality of what they would face when they sought backbreaking work.

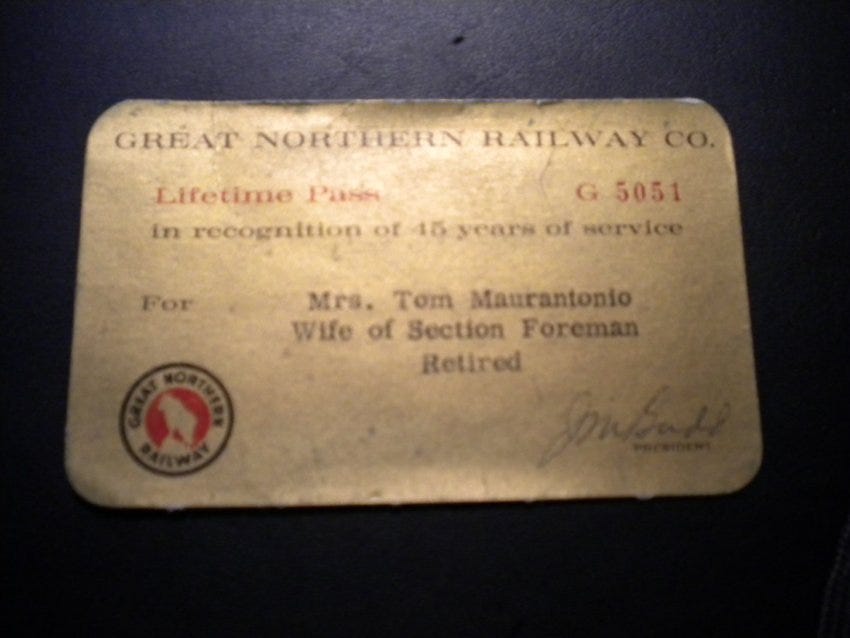

No matter how much they worked, it was never enough pay. Nor were the conditions ever ideal. However, they were well-suited for hard work and railroads fit that bill. They were willing to put in the time to eventually get out from under the padroni and work for themselves, or at the least, someone who would no longer exploit them.

In Idaho, along the Priest River and Bonners Ferry, Italians worked alongside Chinese laborers to build the Great Northern Railroad. But they also built ovens to bake bread, a staple of the Italian diet. I mention the ovens in my book, ITALIANS IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, where the aroma of freshly baked bread must have been a welcome link to the homeland. The Italians built the ovens out of local rock, and then stabilized them with clay. Initially, they were mistakenly called “Chinese ovens”, but archeologists have now attributed the remnants they found to Italian craftwork.

In Oregon, Italians labored for the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company (OR&N), Northern Pacific lines, and eventually, Union Pacific. They helped construct a rail line over the Blue Mountains in northeast Oregon, bringing business to Portland from the Columbia Plateau, Palouse wheat fields, and central Idaho’s mining district. At Garibaldi’s Market, a community hub in Portland for Italians, was where many newly arrived immigrants sought work, including on the railroads.

In 1906 Washington, Italian crews helped lay track through the Columbia River Gorge. This was the beginning of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway (SP&S). They were also instrumental in Northern Pacific’s newly completed line over the Cascades to Tacoma, fulfilling the demand for more timber transport to build the burgeoning towns on the West Coast.

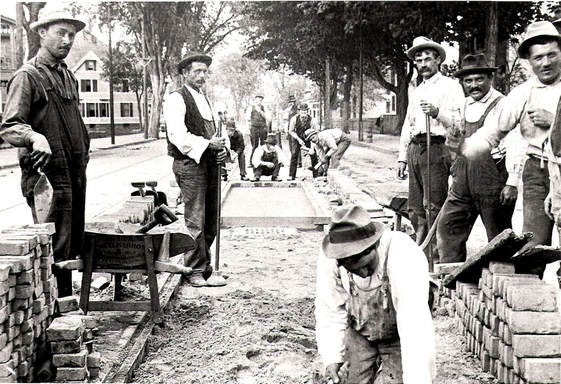

Common jobs involved tie hacking and track walking, where Italian men both hewed ties by hand and crews spiked rails to ties as well as inspected two-mile sections of rail line for obstructions, respectively. Later, handcarts and speeders were used to move quickly to and from work sites, transporting way crews (aka “gandy dancers”), track inspectors, and supplies to maintain the railroad.

When Leland Stanford, president of the Central Pacific Railroad, drove the ceremonial “golden spike” to join the rails of the first transcontinental railroad across the United States connecting the Central Pacific Railroad from Sacramento, California and the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, I like to think there were a few Italians in the crowd. Even if there were none, I hope many were there in spirit. The next time you ride the rails, dear reader, think of the Italians and other immigrants who built the tracks to not only get you where you want to go, but impacted how the West was made.

You can find additional information about Italians and railroads in my recently published book, ITALIANS IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST (Arcadia Publishing).

Order now at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Powell’s, and Bookshop.org.